Topa Topa Brewing Co. Celebrates 10 Year Anniversary on June 14th

/On June 14th, Topa Topa Brewing Co. invites fans for a carnival-themed party at their Ventura HQ & Brewery (4880 Colt Street), followed by a very special after-party concert at their downtown Ventura taproom (104 East Thompson Blvd) headlined by Vetiver and Sam Blasucci (of Mapache). The day and night parties each have their own special offerings, created in partnership with Tierra Sol Institute, the event’s 1% for the Planet nonprofit beneficiary.

Topa has grown from its humble beginnings at its original location in downtown Ventura into an expansive, state of the art production facility, packaging hall, taproom, event venue, and beer garden just a few miles south on Colt Street. Topa now has five locations in Ventura & Santa Barbara counties, and distribution across Southern California and the Bay Area.

Since 2015, Topa has packaged over 12 million cans of beer and donated nearly half a million dollars to 1% for the Planet partners. This, and other cumulative factoids, are featured on the can labels of their limited release 10th Anniversary IPA, named “Topa Is Ten” which will be available exclusively at the anniversary event.

The beer is the first of its kind for Topa, carefully blended with select hop-forward projects to make Topa is Ten a veritable brewmaster’s cuvée. Topa is Ten combines Chief Peak IPA, Blue Heaven IPA, Level Line Pale Ale, and Huckster Double IPA into one bold, celebratory, expressive IPA with layers of zesty grapefruit and tangerine up front, a floral mid-palate, and a dank, slightly tropical finish that lingers just long enough.

Anniversary attendees will have a chance to learn more about this beer during the Founders Session Tour & Tasting, a ticketed special activity within the anniversary celebration that includes a tour of the production facility with co-founder Jack Dyer, a guided tasting of rare archive beers with co-founder Casey Harris, and a take-home goodie bag that includes a 4 pack of the anniversary IPA.

Festivities will include:

Food & dessert ranging from fair food to fancy, including funnel cake & frozen yogurt, oysters & dumplings, and family-friendly options

Carnival-themed attractions & activities benefitting select 1% for the Planet partners - petting zoo, dunk tank, climbing wall, face painting

Live music & DJs from noon til 5 PM at the Ventura HQ & Brewery outdoor garden

An after-party benefit concert with Vetiver, Sam Blasucci (of Mapache), and Farmer Dave & the Wizards of the West - Doors 6P, Show 7P. Tickets $15 available at topatopa.beer/products/pre-sale-anniversary-after-party-at-thompson.

Founders Session Tour & Tasting - a ticketed, behind-the-scenes experience led by Jack & Casey. Spots are limited and guarantee a 4-pack of Topa Is Ten anniversary IPA. Presale tickets now available at topatopa.beer/products/topa-is-ten-vip-ticket.

Brand new Topa Taproom merchandise, including collectible glassware, regional hats, and customizable Father’s Day gift bundles

ABOUT TOPA TOPA BREWING CO.

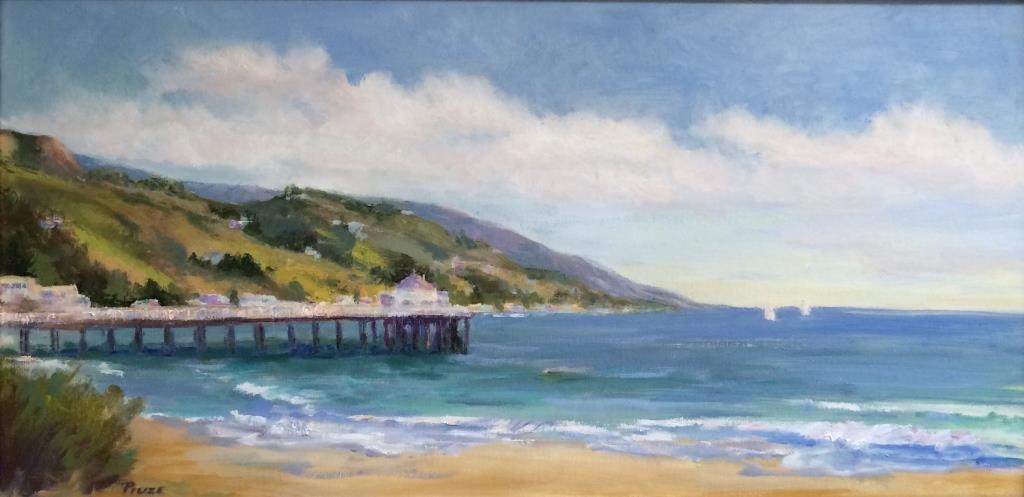

Topa Topa® Brewing Co. was founded in 2015 in Ventura, nestled between the Topa Topa mountains in Ojai and the salty shores of the Pacific Ocean. With five taprooms along California’s southern central coast, Topa Topa is upheld by a trifecta of values: quality, craftsmanship, and community spirit. This means using the freshest ingredients, working with the most skilled brewers around, and thriving on uplifting and unifying our community. Topa Topa is a proud member of 1% for the Planet, donating at least 1% of annual sales to local, approved environmental partners.